︎︎︎ Back to Desktop

Despite

My Skin Colour

(Introduction)

Figure 1. Unknown. Cidade de Guatemala Capital of Guatemala. March 2018. Geografia Total. www-geografia.blogspot.com/2018/03/Cidade-de-Guatemala.html

Mamá Guatemala

As a mixed-ethnicity person of colour and female assigned at birth, I have inevitably been involved with social obstacles and problems since I was a child, especially those that revolve around social inequity based on skin colour. Subsequently, the presence of discrimination and racial hegemony has made me feel concerned, angered, intrigued, and fatigued. Growing up, I noticed myself gravitating towards criticism through visuals, especially during my teenage years when I decided to become a graphic designer and enthusiastically fantasized about influencing social issues through visual art. However, these were fantasies that reflected and relied on my unacknowledged insecurities and the necessity to be accepted and validated despite my skin colour. I understood that I was at a disadvantage due to my position as a female of colour from a country in the Global South but did not grasp yet the concept of revolting against hegemony. Instead, at a younger age, I thought that rebelling against my condition as a girl of colour, meant that I could be the pretty white person I was told by the society around me I should be, regardless of my dark skin.

Eventually, while studying for my BA in Europe, I entered a diaspora that exposed my perspective to a turbulent display of discrimination that challenged my bright-eyed fantasies. Consequently, I decided to voice my concerns about the lack of representation and consideration of people of colour outside the dogmatic western point of view. This series of life changes did not unfold by themselves; accordingly, these were decisions I took because I felt like I had no other choice. My intersectional position pushed me towards them as the perspective of my present self looked back and recollected my race-related experiences.

While I was growing up, my family and I used to travel around the rural parts of the country quite often. This habit broadened my siblings’ and my perspective about many ongoing things in indigenous communities. My mother wanted to develop our perspective on life by bursting our middle-class bubble and showing us the state of the country outside of the privatised and economically privileged sphere that encloses the suburbs. On one occasion, while taking a stroll through the department of Chimaltenango with my sister, we bumped into one of many derelict structures in the town of Santa Apolonia. This one was a kindergarten, quite a charming one. Despite its charm, all I could focus on was the small banner hanging above the door. It read "Kindergarden" in big Arial letters, an anglicised version used in the United States of the original German word. Naturally, the text was on top of a picture of what resembled a kindergarten–it seemed to be a stock photo. The picture displayed a group of white children around a table decorated with toys. I was not surprised; however, I was sceptical about the reason why this picture had ended up in this context. The eery realization that this image had been accessed through the internet,

then downloaded,

edited,

printed,

and finally hanged up in a town,

in a country

in which more than 41% of the population identifies as Mayan (INE Guatemala, 2018)

was hard to acknowledge.

The inappropriateness of the stock kindergarten image was the starting point of a series of recollections that evoked the times I had experienced the same kind of mismatched visual scenarios. Despite the initial shock of finding this image in such a remote place, I understood that such images are something that we, the inhabitants of the postcolonial cities, have embedded into our visual culture. Consequently, many of us, Guatemalans, have been taught to accept this as the norm while living in the metropolis and its surrounding areas, since this is something that one encounters generally. Even more so, during the last two decades, the internet has granted the market a vast amount of visual material that has allowed the lack of ethnic representation to be not only perpetuated but exponentially increased.

Concurrently, it is impossible to ignore the function and impact that the Web has on the current ways of visual language, and the phenomena that come with it. Namely, the impact of western information technologies is visible through the growth of colonized and Eurocentric attitudes–and quite evidently, on digital stock photography, which has significantly shifted visual culture through neoliberal systems. In fact, this phenomenon insists that colonialism no longer inhabits one dimension but instead lives between dimensions and naturally uses digital technologies as tools. As a result, Guatemala is covered in material that enforces visual neocolonialism and therefore visually exhibits the systematic faults that marginalize the disadvantaged, especially those of indigenous background–this is flaunted in urban spaces, where neoliberalism is sacrosanct.

Thus, quite tardily, I became aware that the dogmatic use of western images has become the default of visual communication and moreover, the use of white as the default ethnicity. Like many other shared postcolonial aspects of Latin America, this clear yet intentionally dismissed struggle revolves around the forceful exploitation from the West. Western visual ideals have become the most accessible and preferable figure to use, and therefore, constantly manifest in non-western physical realities. This phenomenon primarily appears as another consequence derived of colonization and the centuries of ethnic shaming and western glorification that come with it. However, it seems to stem also from the fluid transnational nature of the cyber world and its tight relationship with the physical realities.

Content Overview

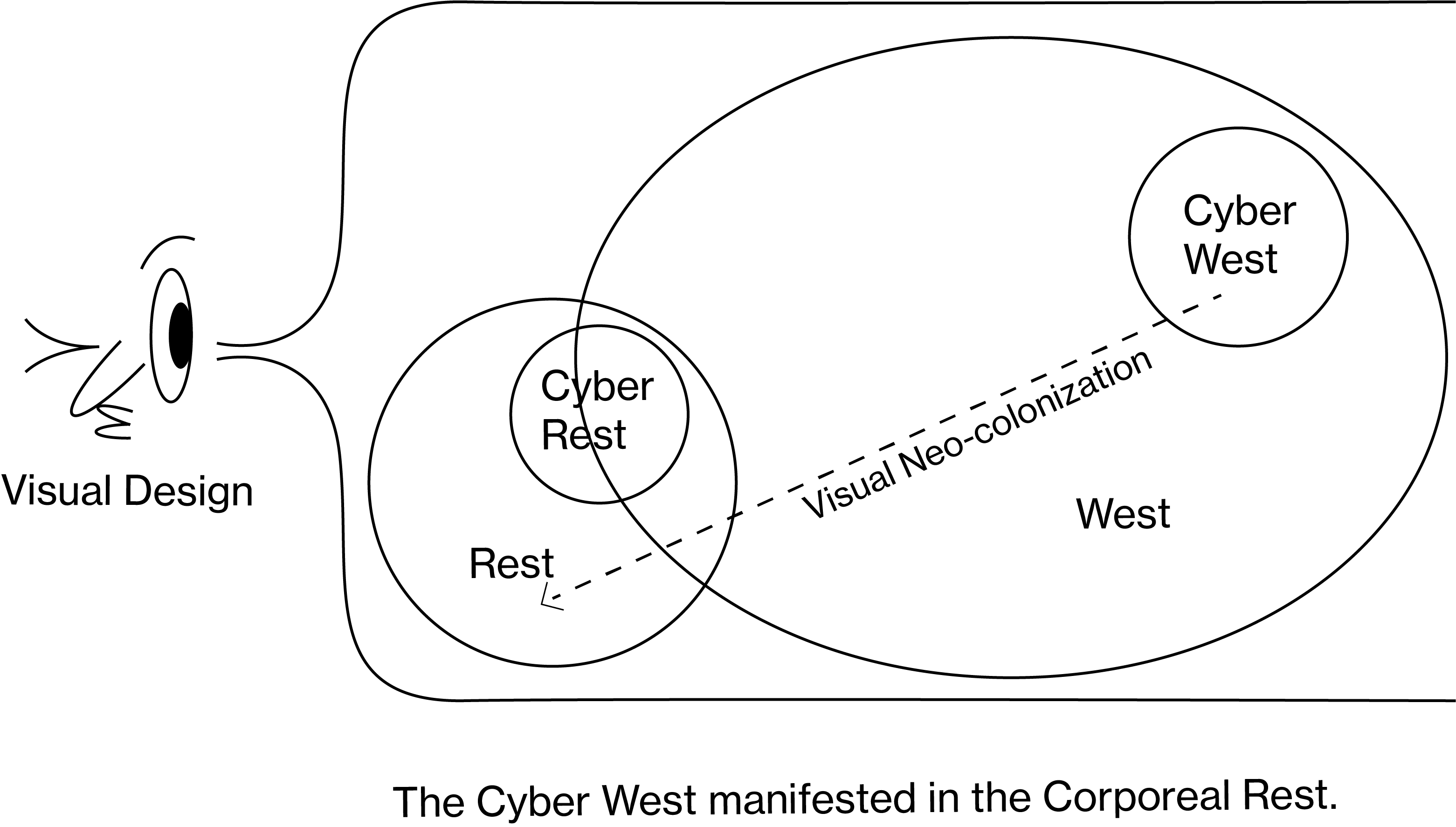

This research aims to interpret a neocolonialism and visual communication design issue that unravels between the physical dimension and the cyberspace. It intends to answer the question: how is digital stock photography contributing to the colonization of visual communication in urban Guatemalan spaces? Ultimately, the focus remains on the lack of representation of people of colour in visual culture and how it became a standard in Latin America, and more specifically, in Guatemala. In other words, what I refer to as the Cyber West manifested in the Corporeal Rest. The existence of this research and its reproductions work as an act of protest against this phenomenon–it aims to challenge its actuality by acknowledging the causes through a theoretical framework and visually exhibiting the consequences through visual autoethnography. Therefore, the thesis does not follow a solutionist path, instead it builds an introspective and critical approach.

In addition, despite the political, sociological, and historical sources of the theoretical framework evaluated in this research, the main objective is to construct a substantial context for the better analysis of this phenomenon through a visual communication design point of view (see fig. 2). I believe that in this research I will contribute to the research gap that lies between the colonial ways of academic theories and the embodied knowledge that is a real consequence of these theories in practice. Also, I will contribute to the existing decolonial visual communication knowledge that is often overseen by Eurocentric design practices. This phenomenon does not exist without the loaded colonial history that comes with it. Therefore, the theoretical framework will briefly clarify what I considered some of the most relevant connecting points to understand the current condition of visual neocolonialism in Guatemala, and by extension, in many other lands of the Global South. By acknowledging the limits and boundaries of this thesis, I would like to shed light on the fact that the analysis does not explicitly include many of the connected social, physical and systematic issues that are equally as relevant and that continue to be perpetuated by the hegemonic state of the world. Nor does it offer a concrete or practical solution to be implemented in visual communication design.

Figure 2. Research approach of “The Cyber West manifested in the Corporeal Rest”

In the following chapter, ‘Contextualizing Hegemonies: Theoretical Framework’, I discuss the historical points that define the context in which the current systems were originated in Latin America in a chronological narrative. Starting with subchapter ‘The Beginnings of Race in Latin America’,I will discuss the starting points of Race as a concept and its role in the colonization of Latin America. After that, in subchapter ‘Global Capitalism in Guatemala’, the relationship between transnationalism, capitalism and neoliberalism is analysed and exemplified through history and the case of the United Fruit Company in Guatemala. Soon after, subchapter ‘Postcolonialism and the Cyber West’ introduces the concepts of postcolonialism and digital colonialism. Following, ‘Visual Neocolonialism’ splits into two connecting parts that analyse visual factors in a postcolonial context: ‘Advertising corrodes visual communication design’ and ‘Stock photography as western ambassador’.

The 4th chapter, ‘The Cyber West Manifested in the Corporeal Rest’, divides into 3 parts that build the research methodology. ‘Decolonization of the self: Visual Autoethnography’ clarifies the use of visual autoethnography as a relevant research methodology; ‘India: Personal Background’, the first part of the visual autoethnography, narrates my personal connections and histories in relation to the phenomenon being researched; ‘Neo-colonial -Liberal Landscapes: Evidencing Visual Neo-colonialism through Guatemala’, the second part, will analyse a recent personal image archive of selected urban spaces in Guatemala.

To conclude, the 5th chapter contains the analysis and discussion of the findings of the research in relation to the theoretical framework. Finally, the conclusion chapter will locate the thesis within the existing body of knowledge, provide a few final remarks and make suggestions for further research. In brief, The Cyber West manifested in the Corporeal Rest is an MA thesis that interlaces theoretical, critical, social, and visual arguments. It seeks to create a protest against the colonization of visual culture by acknowledging the oppressive consequences created by the fluctuation between digital stock photography and its manifestation in the tangible world outside of ‘the West’.

︎︎︎ Previous Chapter Next Chapter ︎︎︎