To understand the current state of visual culture in Latin America, we

must look at the key systems established during the colonization of America. At

present, time and revolution have granted us the circumstances to look back at how

these systems have directed and paved the way for the western structures of

power to evolve and expand. In other words, reconsideration is fundamental to recognizing

the consequences that we face at present. Currently, there is a substantial

number of discussions, social movements and research efforts that involve postcolonial

theory, intersectional feminism, and decolonization, to name but a few. Next,

this chapter will highlight a fraction of crucial historical, economical, and

social elements, with the aim to build the context in which the current Latin

American Eurocentric culture developed, and more specifically the Guatemalan

urban visual culture.

-

The Role of Race in Latin America

-

Global Capitalism lands

in

Guatemala

-

Postcolonialism and the Cyber West

- Visual Neocolonialism

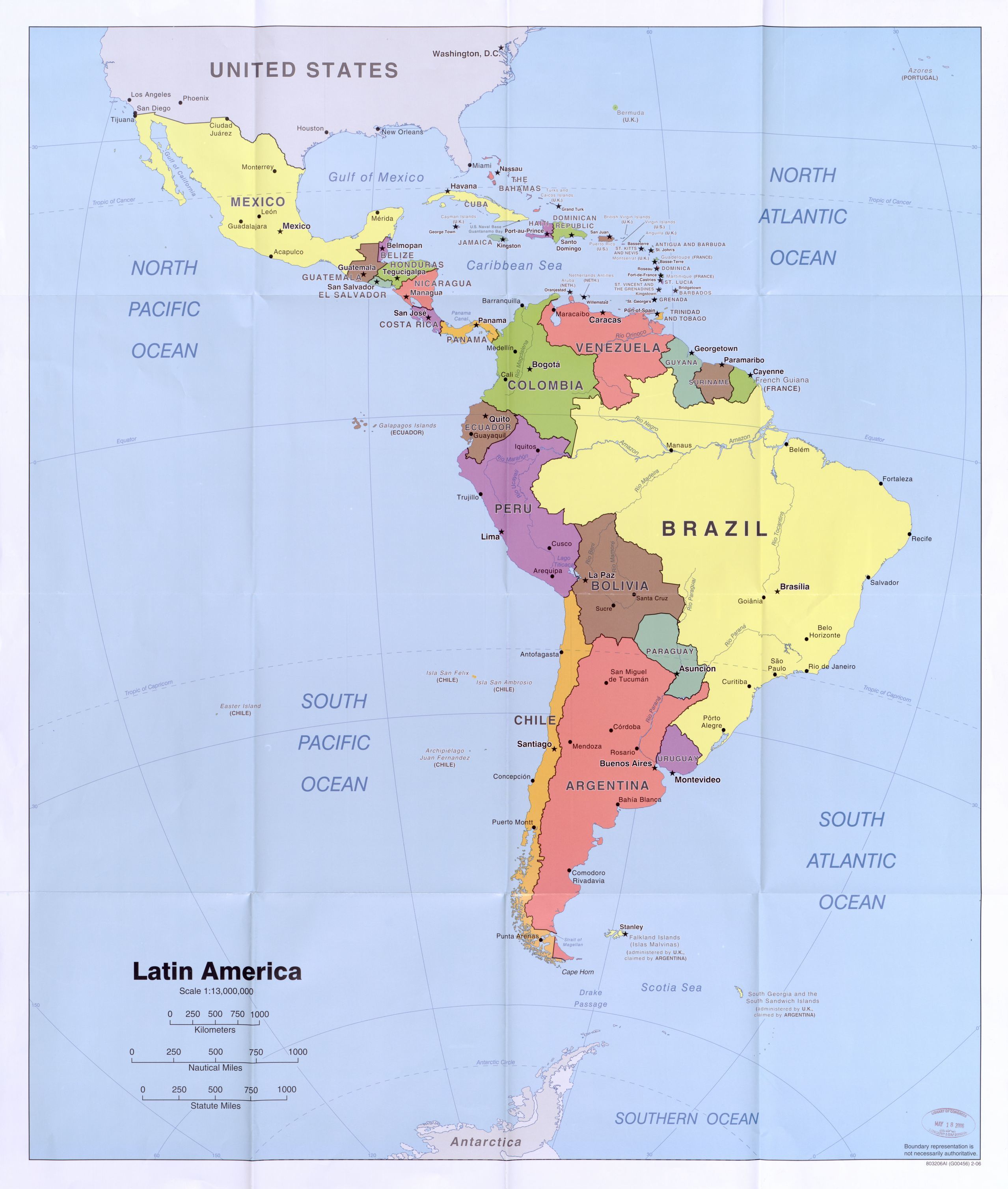

Figure 3. United States Central Intelligence Agency. Latin America. [Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency, 2006] Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2006627988/>.

The Role of Race in Latin America

The history of the Spanish colonization of the Americas began with the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492. In his essay, Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America, Aníbal Quijano discusses the two main axes, that supported (and continue to support) the colonial models of power. According to Quijano, the first axis was built by the creation of the idea of race.

“The idea of race, in its modern meaning, does not have a known history

before the colonization of America.”

(Quijano, 182)

“All concepts of race are always concepts of the body (…).”

(Dyer, 20)

(Quijano, 182)

“All concepts of race are always concepts of the body (…).”

(Dyer, 20)

Race is a means of categorizing different bodies and systematize differences and relate them to worth (Dyer, 20). Race ‘naturally’ placed the phenotypic traits of colonized people in an inferior category–subsequently, the colour of the colonized became an index of their assigned inferior racial category (Quijano, 182). The logic of this categorization granted colonizers the legitimacy to perpetuate their exploitative structures of power by creating an almost sacrosanct positioning between dominant and dominated– this position was validated by the imposed ‘natural’ fact of race (183). Casta paintings (fig. 3) are a visual example of the colonizers’ imposition of race. These images meant to visually communicate a hierarchy and a clear division between the self and the other through a taxonomic categorization that surged during the 18th century, objectifying those who were not Spanish or Creoles.

“In their visual organization these paintings reproduce colonial anxieties about race and the elaborate systems of categorization and control designed to alleviate those anxieties. They attempt to make truths about miscegenation in the colonial context through the representation of raced bodies. However, the truths being made are complex truths, shot through with conflicting allegiances and readable in terms of multiple identifications.” (Olson, 312)

Figure 4. Unknown. Las castas. Casta painting showing 16 racial groupings. 18th century. Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Tepotzotlán, Mexico, Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4642698

The second axis consists of the control of resources, labour and production and the capital-salary relation within the world market (183). It abides the creation of a systemic racial division of labour that would make wages exclusive to whites and would assign certain forms of labour to a specific race. This model of production power was implemented as a technology of domination and exploitation. This validated, according to Eurocentrism, the natural state of race and labour through the association of non-waged labour with dominated “inferior” races (185). Through the perpetuation of market, resources, production and cultural control, Europeans then viewed themselves as the culmination of civilization, as the “developed”, and as the sole protagonists of modernity. They cultivated this dogmatic position through the global model power they built, cornering the “others” into an inferior position (193).

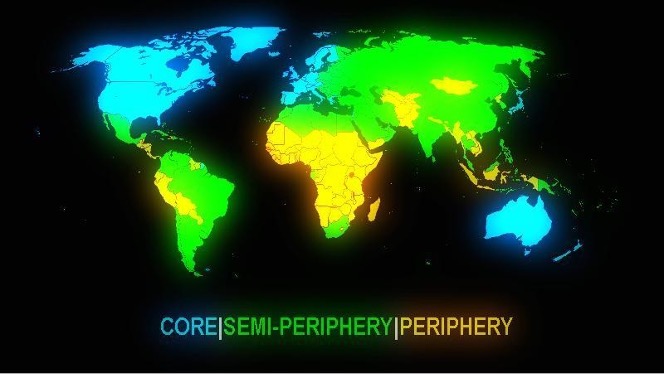

The colonial relationship between Europe and the peoples of the rest of the world then demanded new geo-cultural identities. These identities were based on the European’s own notions of knowledge and their ethnocentric perspective of themselves and others, absorbing subjectivity (Quijano, 189) (see fig. 4). “This binary, dualist perspective on knowledge, particular to Eurocentrism, was imposed as globally hegemonic in the same course as the expansion of European colonial dominance over the world” (Quijano, 190).

Figure 4. The Eurocentric

perspective

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎

Global Capitalism lands in Guatemala

“The rain that irrigates the centres of imperialist power drowns the

vast suburbs of the system. In the same way, and symmetrically, the well-being

of our dominating classes— dominating inwardly, dominated from outside—is the

curse of our multitudes condemned to exist as beasts of burden.” (Galeano, 3)

Figure 5. My visual interpretation of the previous quote from ‘Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent’ by Eduardo Galeano.

A straightforward connection between the assembly of the hegemonic models of power and the racist classification of global capitalism is reflected in all former colonial territories and their colonizers. As Eduardo Galeano states in his work ‘Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent’, Latin America’s underdevelopment history is an essential part of the development of world capitalism––meaning that the poverty of this cluster of colonized countries has always led to the prosperity of the West— in other words, our wealth has generated our poverty (2).

The travel that Spain’s catholic rulers financed and would unintentionally take Christopher Columbus to America, was intended to fulfil the desire for direct access to an abundance of resources (12). Europe was not looking for America, but it was looking for abundance, which it found. Even before colonization took over the Americas, we were doomed to exploitation. Capitalism in Europe started around the same time as the transatlantic colonial crossings–Spain and Portugal started stablishing colonies c. 1500 (Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia). It started as a system to widen colonialism and exploit the resources that were taken away from the Americas through slavery and pillaging of natural resources (Pater, 31-32).

The evidence of the use of western economic growth as an excuse for divesting and striping resources, politics, and indigenous life and culture from a globally less powerful country, can be clearly seen in Guatemala. Despite the independence of Guatemala in 1823, the country was far from stopping being an exploited colony. In this region, a white ‘elite’ built by oligarchs of Spanish, British, Scandinavian, and German origins ruled most of the land for centuries post-colonialism (Chapman, 54). This historical fact is still evident in the current distribution of wealth inside and outside of the country. Namely, 8 out of 10 people in rural municipalities in Guatemala live in poverty–where most of the indigenous peoples inhabit (Justo).

Western privilege and oppression did not limit themselves to originate from Europe–soon the United States of America joined the list of uncertainties for Central America. Among many precedents, one stands out as a clear example of hegemonic hierarchies:

Banana Republic (Henry, 132) is a term that described lands that were invaded and exploited by UFCO (United Fruit Company)–Guatemala was one of them. Founded in 1899, the American company maintained market dominance of Latin American territories through the control and hoarding of land which blocked indigenous people from their right to that same land. UFCO claimed ownership by inserting themselves into the Guatemalan political system (Chapman, 124). According to Schlesinger and Kinzer, UFCO infiltration got them absolute power over the telephone, telegram, the Atlantic harbour, and the monopoly of banana exportation (12). After many years of human and resource exploitation by the UFCO, Jacobo Árbenz was elected president in 1951 (Sabino 127). During his government, he decided to stand up against the monopoly and give back part of the land to the indigenous people of Guatemala. This act was used as an excuse to make the privately-owned company work with the US government to overthrow what they labelled a “communist threat” and start a rebellion (Pater 227). This led to decades of internal conflict and thousands of lives lost over the refusal of further monopolization and expansion of a US company.

Figure 6. United Fruit Company. “United Fruit Company (Chiquita)”. Antique stock certificate from the United Fruit Company dating back to the 1960's. Ghosts Of Wall Street, https://ghostsofwallstreet.com/products/united-fruit-company-chiquita

Figure 7. Chiquita. Easy Thanksgiving Pie with Chiquita Banana. 2020. Chiquita. https://www.chiquita.com/recipes/cake-desserts/easy-thanksgiving-pie-with-chiquita-banana/

Today, we can identify the UFCO as Chiquita–in the form of a sexualized smiling Latina woman with a fruit basket on her head (Pater, 224). Chiquita was allowed by global capitalism to use visual communication to persist and continue to market bananas as a wonderful breakfast food while covering their violent political coups (Pater, 228). Its rebranding and public relations have allowed it to continue as a contemporary healthy snack in a neoliberal economy (see fig. 7).

Guatemala, like many other cities in Central America, has been objected to processes part of a hegemonic and transnational agenda of neoliberalism and polyarchy (Robinson, 89). The imposition of a transnational agenda signalizes a transition to global capitalism–which promotes a global culture of hyper-individualism, competition, and consumerism (Robinson, 93). Neoliberalism is a system that was put in place by economical elites around the world as a response to the threat of socialist alternatives, it proliferated throughout the world from the mid-1970’s onwards (Harvey, 9-15); naturally, it has redistributive effects and increases social inequality as a persistent feature. The neoliberal structure implementation in Latin America has resulted in an upward distribution of wealth shifted outwardly from the domestic to the global economy, thus resulting in a growth of inequalities under globalization (Robinson, 91).

The macro-structural nature of global capitalism has left indigenous cultural issues away from any belief in inclusion and representation. There are no grounds in capitalism for personal consideration, in other words, it is the negation of particularity (Rosales, 23). Under the capitalist neoliberal order in Guatemala, indigenous peoples are structurally restricted to act and are blamed for it. As a result, very few indigenous peoples are given the chance to question their position within an oppressive system that actively restrains them from any type of progress. They are confined to the role, assigned to them by colonialism and capitalism, of peasant workers for the globalization lords. A few individuals manage to overcome a devastating number of obstacles and are praised for escaping poverty–these cases are used as an excuse to perpetuate unequal privilege-based wealth distribution. Admittedly, in capitalism money means production, production means value, value means achievement and, achievement means self-worth. Moreover, “people who fail in the neoliberal achievement-society see themselves as responsible for their lot and feel shame instead of questioning society or the system.” (Han, 21). Hence, not only are indigenous people still suffering the social and representative consequences of colonialism but also are being crushed by the development of global capitalism and neoliberalism, among other factors.

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎

Postcolonialism

and the Cyber West

The structures of power that colonialism built for centuries have caused an array of complicated and intersectional issues worldwide, most significantly inside the lands that were invaded by colonial powers. Correspondingly, postcolonialism displays how the range of tools for oppression–provided by the colonial era–is extensive and persists to be exploited by those who continue to benefit from their use. Equally important, postcolonialism acknowledges that the end of colonialism as a political relationship did not end colonialism as a social relationship (Anastácio 2). From the perspective of the academic world, Professor Duncan Ivison suggests that postcolonialism should not be confused with the claim that the current state of the world is devoid of colonialism, in fact, new forms of domination, subordination and global empire arise with time (Postcolonialism).

To understand the groundwork of decolonisation efforts in contemporary circumstances, one needs to acknowledge that information technologies and systems have amplified the aftermath of colonialism through time. Peter Hulme has written his interpretation regarding the emancipation from colonized systems in the book Coloniality at Large: Latin America and the Postcolonial Debate arguing that “Nothing in the word ‘postcolonial’ implies an achieved divorce from colonialism; rather, it implies the process of breaking free from colonialist ways of thinking’’ (386). In other words, Ivison and Hulme argue that postcolonialism naturally acknowledges that the need to emancipate from the contemporary dogmatic notions funded by colonialism is an evolving process.

As new technologies emerge and colonialism takes on new forms, we must turn our heads to one of the most powerful manmade networks on Earth. In a similar fashion to globalization and transnationalism, the internet brought its very own imposing language to the world. Undoubtedly, the internet has revolutionized communications at a global level. However, the leverage and benefits have been in favour of western countries and their private companies (Radu 79). Increasingly important, is the position of the United States, not only in the formulation of the internet as a network but also as a pioneer of digital colonization. Henceforth, it is significant to question how the internet governance model serves as a platform for the US to influence other nations.

It is worth noticing that the initial form of the internet was funded by the US Defence Department Advanced Projects Agency (DARPA) and deployed with the help of the US National Science Foundation (NSF) and various academic funds in Europe–it became commercially usable by the beginning of the 1990’s. Moreover, the world-wide-web was conceived in Switzerland by an English national. Thereafter, when faced with the consultation of a multilateral approach to internet governance, the US government imposed a national entity-based regulation (Radu 80). In the following years, it was proven that there are evident imbalances between who has more control over technology, more exactly the internet, and who has been assigned a passive position as a consumer with little to no autonomy. The imbalances of internet governance exist in the Global North; however, it is hardly comparable to the telecommunications inequality the periphery of the world experiences (Anástacio 5).

“Imperialism can be defined as the policy of extending a nation’s authority by territorial acquisition or by the establishment of economic and policy authority over other nations. The current Internet governance model fits well into this definition (…)” (Radu 86). Paradoxically, the internet has provided a bigger space for minorities, but it has reinforced inequalities and western worldviews. This paradox is a clear example of digital colonialism. Digital colonialism intends to mark the relationship between who or who is not relevant in the global society inside and outside of cyberspace (Anástacio 6). This machinery is exercised through centralized ownership and control over the digital ecosystem, which instead of conquering land, colonizes digital technology. Like geographical colonialism, digital colonialism allows western powers, more significantly the US, to plant infrastructure in the Global South that is engineered for their own needs, enabling cultural, economic, and capitalist domination (Kwet “Digital Colonialism: US Empire and the New Imperialism in the Global South.” 4-7). Despite the potential use as a tool that reduces barriers and promotes development, the internet has become one of the most powerful tools for neo-colonialism.

Digital infrastructure is dictated by three core pillars: software, hardware, and network connectivity. More significantly, software has a key influence on the behaviour, policies, and freedoms of people with access to digital technology. Overall, the Cyber West exerts digital domination by the means of centralization tools, which gives it control over communications–by way of code. Mechanisms like copyright, which protects the monopoly of content production in the name of intellectual property rights, further alienate the Global South from true digital representation (Kwet “Digital Colonialism: US Empire and the New Imperialism in the Global South.” 8-12).

From a postcolonial perspective on cyberspace, we must criticize the western rational culture that reproduces the colonial relationship between giver and receiver (Anástacio, 3). The internet is based on a giver-receiver model in which the receiver pays. Analogous to this, is how the international connections dynamic benefits by penalizing Global South countries for accessing more content than the one they produce. Consequently, the Global South will receive less information than the Global North simply because the North has more money to spend. Moreover, the internet works in favour of a neoliberal agenda by allowing certain aspects of the internet to be governed by the private sector in which less developed countries hardly get fair acknowledgement (Radu, 85).

Through global capitalism criticism, we must recognize how influential is neoliberal communication. According to Byung-Chul Han, the careful administration of bodies and management of lives through neoliberalism facilitates disciplinary power–which is a type of normative power that subjects a set of rules, commandments, and prohibitions and eradicates anomalies (42). Disciplinary power extends to disciplinary technology which subsequently reaches the mental sphere outside of the physical realm (42), transporting the norms encouraged by the digital realm to the physical dimension. This technology augments the influence of hyper-individualism, one of neoliberalism’s key features–which ultimately isolates us from our communal surroundings and instead locks us up in a private sphere sculpted by the western eye. Concurrently, the freedom offered by the internet and the digital world has become an exploitative neoliberal device that converts our behaviour into numbers, and those numbers into strategies for profit (21-25).

“Smartphones represent digital devotion – indeed, they are the

devotional objects of the Digital, period. As a subjectivation-apparatus, the

smartphone works like a rosary – which, because of its ready availability,

represents a handheld device too. Both the smartphone and the rosary serve the

purpose of self-monitoring and control.”

(Han, 69)

(Han, 69)

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎

Visual

Neocolonialism

The aftermath of colonialism can be immediately identified in visual communication and visual culture in the corporeal rest. The lack of connection between the images that are displayed on visual outlets and the context in which they exist is evidently incongruous. As it can be observed later in the research methodology, visual communication in the Guatemalan urban environment has been mostly absorbed by the representation of western worldviews, particularly those concerned with people’s physical traits or, most specifically, what they should aspire to be. For the purposes of this thesis, the focus remains on one of the most problematic of aspects: ethnic representation. The ways in which visual culture, particularly commercial work e.g., advertising, inevitably exhibit the lack of consideration for ethnicities outside of the western ideals are, to say the least, striking. However, I must acknowledge that ethnicity is just one of the bodily consequences to be dealt with in Postcolonialism. Ethnic discrimination does not unfold by itself, nor it is isolated from e.g., patriarchy or heteronormative oppression.

︎︎︎ Advertising corrodes visual communication design

As realities merge and the Cyber West manifests in the Corporeal Rest, visual culture mutates under the influence of global capitalism and its digital amplification. In a brief timespan, physical public spaces have been reduced and adjusted to the imposing force of capitalism and its need for consumerism. Moreover, the type of consumerism we are experiencing at this time is not only no longer proportional to our basic needs (Pater, 233) but has also extended to the neoliberal needs that only exist within the capitalist society. Neoliberal policies, including those that dictate government services to be financially profitable, are responsible for such transformations. This circumstance is evident in the fact that many cities, including Guatemala, depend on the revenue that profitable visual communication brings into their economy. Consequently, most of the jobs available for visual communication designers serve marketing strategies or fall into the purpose of profit as its main objective–thus making the advertising industry the leading “creative” business (Pater 183).

“Advertising is the very foundation of an economic system that seeks to

expand until it has absorbed everything in its path.”

(Pater, 232)

(Pater, 232)

Advertising is so pervasive that we move through physical and cyber spaces surrounded by the consumerist language and find it hard to make a distinction between communications and sales–advertising is omnipresent (Pater, 183–232). This extends to the digital dimension, where we are surrounded by ads, fishing, click-bait, among others–all communicated through visual and written narratives. Overall, advertising is a relatively conservative industry with conservative origins. Its methods combined with the fear of losing clients have produced a corporate culture with a restricted expression of creativity. Nevertheless, neoliberalism claims to have embraced creativity–but rather than embracing it for its freedom of expression or its aiding potential, it was embraced as a way of competition and adaptation that would ultimately lead to a bigger profit–this principle was naturally applied to advertising. For instance, the misleading claim that only free-market competition grants true innovation seems unsupported by the lack of variety in much of design and advertising, which at present is vastly homogenous. What’s more, advertising tends to commonly portray the wealthiest people in society as an aspiration and creates normalities that benefit its clients, perpetuating the doctrine of consumerism. The lifestyle represented through advertising in various media, including the internet, reaches the periphery of the world in an imposing way claiming to be the only truth (Pater, 190-207). Accordingly, and remaining loyal to the neoliberal nature of advertising, these depictions of life are inconsistent with the reality they manifest in, generating new needs and normalities that do not fit within the receiver’s context. In fact, Pater proposes that if society is a series of visual social relations, then advertising and graphic design should be regarded as the shapers of societal organization (203).

In relation to the invasion of visual environments on behalf of advertising, the factor of visual pollution is very influential. “Visual pollutants are defined as any physical barrier that interrupts clear sight line or distracts attention from unique space qualities.” (Cvetković, Momcilovic-Petronijevic and Ćurĉić 103). Visual pollution has a strong influence on the space it inhabits, both on an individual and atmospheric level. Regarding the atmosphere, the loss of the space’s identity is one of the main consequences of visual pollution. It interrupts the relationship between the individual and their surroundings by inserting external influences (Cvetković, Momcilovic-Petronijevic and Ćurĉić 104) which in the case of neoliberal urban spaces, involves the insertion of advertising to further promote consumerism. Naturally, the environment that the neoliberal urban spaces offer its inhabitants has effects on individuals–these effects reflect the nature of neoliberalism and its increase in individualism and self-criticism, discussed previously in this chapter. Furthermore, advertising is known for using psychological tricks to influence the subconscious of consumers and manipulate their behaviour (Pater 189) plus neoliberalism exploits emotions as a way to bring about heightened productivity and achievement (Han 78). As a result, the human psychological state is not only affected by the visual pollution itself, but also by the use of psychological tricks and strategies used within.

Stock photography as western ambassador

Concerning the condition of visual communication design in the neoliberal sphere, the relationship between the written word and the visual input is dominated by profit. The profitable, conventional, and quick visual communication serves as the main instrument of advertising–but how can visual communication design adapt to such conditions? According to Paul Frosh, advertising and marketing make great use of stock photography, which is a global industry dominated by agencies in the United States and Europe (3). For this thesis, when referring to stock photography, I will refer to its online format–since, in the current decade, the online stock archive is the most extensive and accessible worldwide.

In short, stock photography works in a taxonomic way developed for consumer culture. Inside consumer culture, e, the consumption of commodities is the axis by which the viewers are targeted, constructing an industrially manufactured visual environment of complex media societies (2). “Equally, this environment is dominated by the production of visual images both as commodities in their own right and as promotional vehicle for other commodities (…)” (2). The billion-dollar stock photography industry, which will grow $1.2 billion by 2025 (Technavio), has thrived on its quick and inexpensive availability of readymade images, avoiding time-consuming productions i.e., photoshoots (4). Naturally, this quick and easy acquisition means that the stock agency benefits greatly from the acquired rights of the picture purchased from the photographer, who bears the production costs–the agency, archives the selection of virtually free content, sold worldwide over a long period of time (4). Ultimately, photographers and visual artists are encouraged, by the dominating visual image industry, to follow the hegemonic guidelines to conventional creativity and reality depiction in order to get compensated. For instance, a user nicknamed Magda promotes the wide usage of stock photography in current marketing strategies in a blog claiming: “As you see, many photo buyer prefers stock images over custom photography. For marketing and advertising, for social media like Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter, to illustrate a blog post or to add visual impact to an app. Creatives around the world are using stock photos to make it happen.” (The Stock Photo Market: What, Who, How and Where of Stock Photos in 2022)

Stock photography has a choking hold on visual content production, but of major concern is the content and the realities communicated through these images. To begin with, because stock photography originates from neoliberal needs developed in the West, the framework in which the decisions and compositions take place is of hegemonic nature. In addition, the cultural backgrounds of photographers, agencies and intermediaries play an essential role in the perspective and structure the images are built. Moreover, as stated before, the stock photography industry is built to please another industry that is dominated by a capitalist, western mindset. As a result, this type of mass-produced photography encourages the reproduction of formulaic compositions that construct cultural stereotypes of those that do not follow the conservative approach of marketing strategies (Frosh, 5). Furthermore, when demand for diversity is made, the diversity provided comes from a conservative and dichotomic point of view and thus creates further stereotypes. In a study by Athena Papadopoulou, a sample of stock photographs from Getty Images showed that 409 out of 500 images included models of Caucasian ethnicity (28). In addition, it was demonstrated that in most of the images depicting ethnic diversity the Caucasian model holds the centre (31).

“One of the most interesting facts about the stock photo industry is that despite being somewhat narrow in concept, it serves people and companies of all shapes and sizes, and from the most varied backgrounds.” (Magda, The Stock Photo Market: What, Who, How and Where of Stock Photos in 2022)

A substantial number of photographs and images encountered in commercial visual communication design–especially in US advertising, marketing, and graphic design–come from stock photography (Frosh, 7). Because of the previously analysed hegemonic relationship between the US and Central America, Guatemala City has consequently been covered in a massive amount of visual content originating from a western reality depiction and visual content production.

︎︎︎ Previous Chapter Next Chapter ︎︎︎